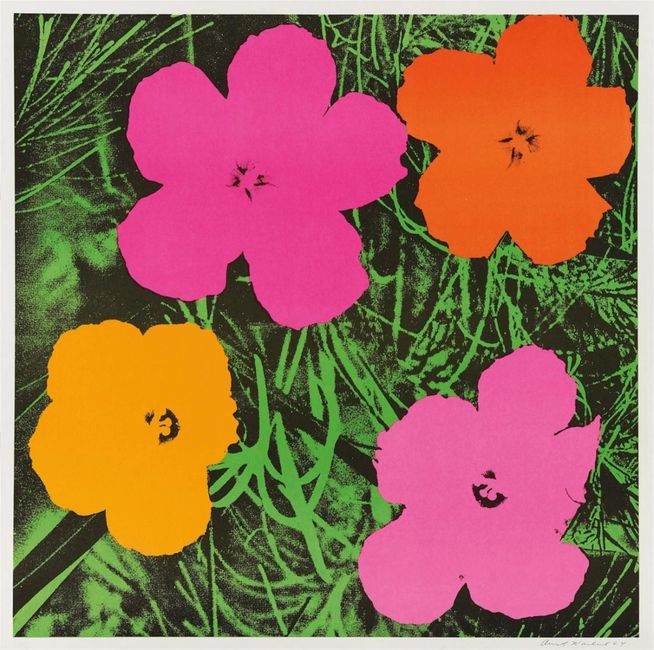

Flowers

Additional Information

The original is created through, color silkscreen print

"Don't think about making art, just get it done. Let everyone else decide if it's good or bad, whether they love it or hate it. While they are deciding, make even more art."

~Andy Warhol

Andrew Warhola (1928-1987) was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to Slovakian immigrant parents, Andrej and Julia Warhola and received his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in 1949. Soon after graduating, he moved to New York City to look for a job as a commercial artist, which he quickly found at Glamour magazine. It was at this time that Warhol dropped the “a” at the end of his last name to become Andy Warhol.

Though he went on to become one of the most successful commercial artists in the city, in the latter part of the 1950s Warhol started to focus on painting, and by the 1960s he was fully immersed in the Pop Art Movement. Having its roots in London in the 1950s and blossoming in the 1960s in America, Pop Art declared the ordinary objects of modern everyday life to be worthy as subject matter.

To better understand Pop art, it is helpful to understand what was happening in America at that time. Trends in the arts mirrored the turbulent social and political climate of the 1960s. A time marked by transformation, optimism, tragedy, and disenchantment, this era witnessed: the height of the civil and gay rights movements, protests against the Vietnam War, the peak of the Cold War, threats of nuclear war, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the evolution of Rock and Roll, the recent proliferation of television in American homes, students protests and the Hippie movement, and has become known as the age of counterculture.

The arts—literature, art, dance, music, and theater—went through a period of significant growth and transformation during the 1960s, and a surge of new artistic movements arose including Pop Art. Growing commercialism in American society deeply impacted this new artistic style and in response, Pop subject matter veered away from “high art” themes of morality, mythology, and classic history. Instead, it aimed to overturn prevailing fine arts values and provide a radical alternative.

Pop artists dove into new imagery that held a mirror up to society and examined its cultural roots. They borrowed images of popular mass culture, the media, advertisements, magazines, movies and popular icons; creating images of images! Their techniques stemmed not so much from a desire to shock as from an urge to exploit the potential of bold commercial graphics. This new artistic style was both familiar and easily understood by the wider public which was a great relief following the elitism of Abstract Expressionism. Prior knowledge of art and artists was no longer required; everyone knew and recognized the imagery. Many art critics, however, were alarmed by the Pop Art movement, uncertain whether it was embracing or mocking popular culture and fearful that it threatened the survival of both modern art and high culture.

Often considered the father of Pop Art, Warhol sought to obliterate the notion of low and high art. His declared enemy was the elitist, subjective, gestural painting of Abstract Expressionism. He instead focused on ideas and images that reflected American culture. To him, paintings were no different from cans of Campbell’s soup; both have material worth and could be bought and sold like consumer goods. By painting these ordinary subjects with intense colors, bold shapes, and unconventional sizes, Warhol challenged viewers to examine his subjects in a new light.

Using the techniques and images he learned as a commercial artist, Warhol began by painting stylized comic strips and advertisements. Later he produced works of repeated images using rubber and wooden stamps and stencils which eventually led him to reproductions made with silkscreen on canvas. As an explanation for abandoning the paintbrush Warhol said, “[painting] suddenly seemed too homemade. I wanted something stronger that gave more of an assembly-line effect.” To emphasize his detachment from any emotive content in these images, he silk-screened them on to canvases in batches, implying that they could be repeated infinitively.

Warhol’s insistence on mechanical reproduction rejected notions of artistic authenticity and genius. The Flower silkscreen series images, like his Campbell’s soup cans, allude to the repetition of mass-produced commodity goods. Flowers, is one of ten in a series based on an appropriated photograph of seven hibiscus flowers published in a 1964 edition of Modern Photography magazine. The photograph was cropped to create a perfect composition of four flowers on a square canvas so that it could be viewed from any direction. Each image in the series was copied and enriched with different contrasting colors, leading the photographer to sue Warhol for use of her photo without consent. The lawsuit introduced questions of authenticity and authorship to Warhol’s’ oeuvre.

The fact that Warhol used silkscreen printing, a mechanical art style typically only used for commercial art, to paint such a natural and dainty subject sets his flowers apart from traditional still-life representations. They are at once devoid of meaning, and teaming with individual meaning placed by the viewer. What, if any meaning do you find in Flowers?

While Warhol was inspired by a photograph rather than direct nature, his hibiscus flowers are a colorful reminder that spring is in the air. We may currently be sheltering in place, but there has never been a better time appreciate the beauty in nature. Take a walk or look outside you window. What inspires you or occupies your current thoughts? Whether it’s a beautiful flower, the shortage of toilet paper, or John Krasinksi’s “Some Good News,” try creating your own Pop art creation. We would love to see it! Please share your artwork with us at emergencyartmuseum@gmail.com and you may be featured on our website.

*abstract expressionism – The term applied to a new style of abstract art developed by Americans painters such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Helen Frankenthaler, and Willem de Kooning in the 1940s and 1950s. Working after WWI, the Abstract Expressionists began to rely on their own particular experiences and visions which they painted as directly as they could. The style is often characterized by gestural brushstrokes or mark-making, and the impression of spontaneity of expression and individuality.

Abstract Expressionism was officially recognized in the 1951 Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America.” The term embraces artwork of diverse styles and degrees of reference to content or subject.

The Abstract Expressionists experimented with unstable, indeterminate, dynamic, open, and “unfinished” forms directly exploiting the expressiveness of the painting’s medium to suggest the particular creative action of the artist – their active presence and temperament. Abstract Expressionist art is often large in scale so that the viewer becomes enveloped in their experience. Abstract Expressionism can be divided into two tendencies:

- gestural painting – (“action painting”) brush painting which was concerned with gesture, action and texture (Pollock, de Kooning, Kline)

- color-field painting – (“post-painterly”) which was concerned with a large unified shape or area of color (Newman, Rothko, Still).

*oeuvre – The complete works of a painter, composer, or author regarded collectively. For example, “the complete oeuvre of Van Gogh.”

*pop art – Art which makes use of the imagery of consumerism and mass culture, with a finely balanced mixture of irony and celebration. Pop art began in the 1950s with various investigations into the nature of urban popular culture, notably by the members of the Independent Group at the ICA (Institute of Contemporary Arts) in London. Pop Art was at its height in the U.S. during the 1960s, where it came as a reaction to Abstract Expressionism and in fresh response to Dadaist notions. The basic concept was that mass-produced consumer goods were taken as the materials of a new art and a new aesthetic of expendability.

*silk-screens – A variety of stencil printing, using a screen made from fabric (silk or synthetic) stretched tightly over a frame. Silk or another fine fabric is stretched tightly over a frame making a screen. Next, a stencil of paper, acetate, or other material is cut to make a design and adhered to the screen. Printing paper is then placed beneath the stenciled screen and ink is pushed through the screen with smooth even pressure using a rubber squeegee. Ink passes through the screen in the open areas of the stencil thus, printing the design on the paper below. For a design of more than one color, different stencils are cut for each color and are printed in layers that must be perfectly aligned.

Copyright © 2020 Emergency Art Museum - All Rights Reserved.

*The Emergency Art Museum claims no ownership, or copyright to any materials found here, or on-site. The Emergency Art Museum functions solely as a non-commercial, non-profit, educational resource for the community. All artwork represented or reproduced, has been done so for educational purposes only under the fair use act.

-Johnny DePalma, Owner / Curator

-Janelle Graves, Art Historian / Museum Educator